|

IIEDWARD BUNKER, SR 1822-1901

|

Website Link Index | ||||||

|

Orson Pratt Brown's Uncle

Edward Bunker, Sr.

|

|

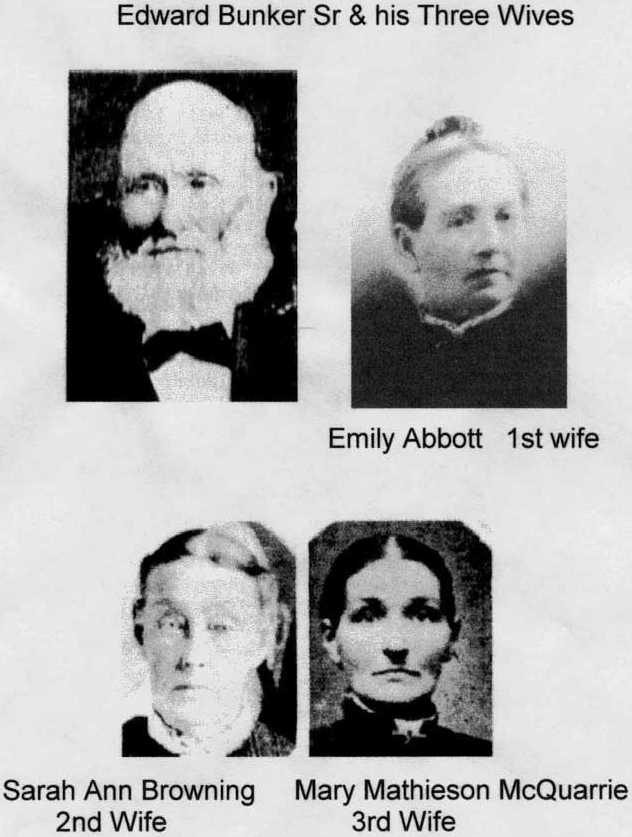

Edward Bunker was born on August 1, 1822 at Atkinson, Penobscot County, Maine to Silas Bunker, Jr. and Hannah Berry. Edward Bunker married Emily Abbott, daughter of Abigail Smith Abbott and Joseph Abbott, also sister to Phebe Abbott Brown Fife, on the 9th of April 1846 in Nauvoo, Illinois with the ceremony performed by John Taylor.

The Annotated Edward Bunker

|

|

Chapter 3 - The Mormon Batalion Chapter 6 - Eastward to England |

Chapter 11 - The Big Move |

In 1894, at age 72, Edward Bunker paused to reflect on his long and full life. He wrote a brief autobiography touching on what he felt were the most significant events. Unfortunately, the story he told was brief, to the point, and lacked the rich detail and emotion that could have instructed and inspired us. But from that autobiography and other information we can piece together the fabric of a marvelous life. His life reached from early nineteenth century New England to the untamed American West and the broad pioneering movement.

He traversed the North American continent, east to west, north to south several times. He spent three years amongst the working class Victorian subjects of the British Isles. He was a frontiersman, soldier, and missionary. With great leadership and knowledge based on practical experience he built roads and communities and skillfully navigated the rugged way. But more important to him than anything else he may have accomplished was his faith and family.

[Note: Quotations from Edward's writings will be included in the text printed in italics and preceded with an "EB".]

EB: I was born in the town of Atkinson, Penobscot County, State of Maine, August 1, 1822. My parents were Silas Bunker [Jr.] and Hannah Berry Bunker. I was the youngest of nine children; seven boys and two girls, whose names were as follows:

[1] Abigail [1801], married Mr. [Samuel F.] Heath;

[2] Nahum [Berry, 1804], married Irene Thayer;

[3] Hannah [1807], married John Berry;

[4] Alfred [1809], who never married;

[5] Martin [1811], married Mary Ann Gilpatrick;

[6] Kendall [Kittredge, 1812], married his cousin, Rachel Bunker;

[7] Silas [1816], died when 27 years old, unmarried;

[8] Sabin [1818] married after I came west so I do not know who he married.

[9] [Edward 1822]

Edward tells little of life in the small New England town of Atkinson, Maine. Going back it is possible to reconstruct the stage on which he played out his youth. Beginning in 1820, two years prior to Edward's birth, several significant things happened: 1) Maine was admitted to the union as the 23rd state, 2) The inland territory of Maine was divided and sold to private individuals, and 3) Silas Bunker, Jr., Edward's father, moved his wife and eight children from the coastal town of Trenton to Atkinson, a new town on the edge of the north woods of Maine. That same year Joseph Smith, a fifteen-year-old boy in upstate New York, claimed to have seen a heavenly vision that would become the foundation for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

In 1820 the population of Maine was about 300,000, mostly scattered along the Atlantic seaboard. The people were sturdy middle class descendents from Pilgrim ancestors mixed with emigrants from various countries. Home, church and family were important. When not tending crops, they were clearing land, sailing, hunting in the woods, and fishing the Atlantic coast or inland waterways.

As towns became more crowded and opportunities for cheap land in the new upstate regions developed, many relocated to the numerous communities that were springing up across the state. Edward's uncle, Benjamin, had taken his family up the Penobscot river about 70 miles from Sedgwick and settled at Williamsburg on the edge of the North Woods. The land was inexpensive and resources abundant. Soon Edward's father and another uncle, Thomas, followed and settled their families at the nearby towns of Atkinson and Charleston, respectively. Atkinson was a small farming community with a population of 250, incorporated in 1819. The town had a physician, Dr. E. W. Snow who had moved to the town in 1818 from New Hampshire and was regarded as a kind generous man and good physician.

When the town was incorporated, Judge Atkinson of Dover, New Hampshire, for whom the town was named, presented the town with one hundred books for a public library. The center of town was called "The Mills" where a saw mill and store were located. There was a church in town and a tavern on the outskirts at Jameson Hill.

Here, in a little farming community surrounded by the north woods, Silas Bunker, Jr. and Hannah Berry welcomed their ninth and last child into the world. They named him Edward Bunker after Hannah's father.

Edward was a fifth generation descendant of James Bunker who had come to America in 1646 from England. Edward's line of Bunkers had slowly migrated from the original Bunker Garrison at Durham, New Hampshire up the Atlantic coast to Sedgwich, Maine and finally inland to Atkinson. Edward's older brothers and sisters were marrying and establishing themselves in nearby communities. Edward must have had relatives all along the New England coast. His father, Silas, was one of eleven children raised in the Sedgwick area and his mother, Hannah, was one of nine children raised in the Trenton area.

During Edward's youth the North Woods became alive with the sound of the axe felling tall trees. Rough and rowdy men flooded into the woods in the winter time to harvest the waiting lumber. Bearded, hairy-chested loggers in red shirts and gray pants, with boots and woolen hats, would leave the summer-time sailing trade to paddle up the Penobscot. After the trees close to the river were cut, the loggers moved deeper and deeper into the forest.

Swampers build roads into the interior. Choppers cut the logs, barkers strip the bark, and teamsters and their oxen drug the logs across the snow to the river. In the spring, logs jammed the Penobscot river surrounding the numerous islands whereon the Penobscot Indians dwelled. Eventually the logs would reach Bangor, Maine's leading lumber port. The population of Bangor went from under 3,000 in 1830 to 8,000 in 1834. It was a town built on the lumber trade, where land speculators, loggers, and the related businesses thrived.

No information is yet available to indicate that Edward's family was ever involved in the lumbering trade. The loggers were a rough bunch contrasted with Edward's people who were close to home and family. But Edward's later ability to build roads and handle an ox-team suggests that he may have had some experience as a youth in the wintertime activity.

In the winter of 1829, Edward's grandfather, Silas Bunker, Sr. traveled the 70 miles from his home at Sedgwick to visit Williamsburg. He was 82 years old and probably visited all three families at the time. On his way home he stopped at Blue Hill to visit his daughter, Jennie, and in the morning opened the wrong door by mistake and fell into the cellar. He was seriously injured and lay near death for ten days.

Not only was Silas, Sr. in serious condition, but Edward's uncle Isaac Bunker, who lived at Sedgwick, became ill at the same time. Isaac died February 11th, 1829 and Silas, Sr. died four days later, on February 15th, 1829. The double funeral and loss of his grandfather must have seemed a strange time for a six-year-old boy.

The census of 1830 counted a population of 418 at Atkinson. Edward was 8 years old and youngest of the 6 boys still at home. His older brothers undoubtedly taught him patience and humility early in life. But, as the youngest, perhaps his mother was protective which endeared her even more to him. In that same year Joseph Smith officially organized the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with six members at Fayette, New York. Though Edward was not aware of this event, it would be of great significance in his later life

The next few years passed with all the natural joys and hard work of a rural small town existence: Exploring the North Wood, White Mountains, and Moosehead Lake, swimming and fishing in Pushaw Pond and Alder Stream.

On April 27th, 1836, Edward's older brother Martin, married Mary Ann Gilpatrick, probably a cousin on his mother's side. Edward's grandmother's maiden name was Gilpatrick. Martin and Mary moved to Trenton, Maine, where most of the Gilpatricks lived

The next year Edward's uncle Tom at Charleston built a boat called the "Betsey Bunker" in honor of his wife and intended for his son, Richard. Richard was 17 and just two years older than Edward. Tom hauled the vessel overland more than 20 miles and launched it in the Penobscot River at Bangor, Maine on the 4th of July. Edward may have watched with keen interest as this modern Noah built his Ark. He may have shared Richard's enthusiasm and silently desired that he too could travel up and down the river.

On April 7th, 1838 when Edward was sixteen his older brother Kendall married Rachel Bunker. Rachel was Uncle Tom Bunker's daughter and Edward's cousin. The family had several instances of intermarrying with cousins and must have been very close as an extended family.

EB: When I was about sixteen years old, Father sold our home and moved to Charleston at which place we lived five years. During our stay there, Father deeded his farm and other property to my brother Silas on condition that he take care of the old folks as long as they lived.

The census of 1840 showed Charleston with over 400 residents. Thomas Bunker (Edward's uncle) and a household of nine lived next door to Kendall Bunker (Edward's brother) and his household of three. Silas Jr.'s residence was some distance from Thomas and Kendall and identified five people living there.

EB: When I was nineteen years old, I left home with the consent of my parents and brother Silas, to work for myself, as Silas owned the property, I felt I ought to have my time. After an absence of two or three months, Silas requested me to come back and live at home as he was lonely without me. He offered me a deed to one-half of the property if I would go back. I refused the offer, telling him it would be a good home for him and he could care for father and mother.

A nineteen-year-old Edward was experiencing the same desire to travel that had taken charge of an eighteen-year-old James Bunker in England five generations earlier.

EB: A spirit of unrest had taken possession of me and I longed to get away. The farm was a good one, consisting of 100 acres of land, good buildings and a nice stock of cattle. Silas felt so lonely without me that he rented the farm and went to Trenton, a distance of sixty miles, to work for my brother Martin. After he got work, he wrote for me to come there, too. As work was plentiful and I could get a job, I went down. A few days after my arrival, Silas was taken sick with filious fever. I stayed with him until he died. Before his death, realizing his time had come and not wishing the property to go back into Father's hands as he was not capable of taking care of it, he wished to deed the property to Martin and myself for the benefit of Father and Mother.

So we had the deeds drawn up and he sat up in bed and signed them. After the death of Silas, Martin made me a proposition which was this: He would pay the funeral expenses and the doctor bills and deed me his share of the property if I would pay him $200 and take care of the old folks. Or he would pay me $200 and take care of the old folks if I would deed him my share of the property and pay Silas' funeral expenses. I accepted the latter offer, which astonished Martin very much. We returned to Charleston, where at my request, he gave Father and Mother a life lease and I deeded him my share of the property.

After this was done, I returned to Atkinson, bought a small farm of my brother Kendall and took a notion to visit my brother Nahum living in Boston. Accordingly, Brother Sabin took myself and a load of shingles to Bangor. I sold the shingles and worked my passage to Plymouth.

I visited Nahum in Braintree and he proposed we visit Alfred, who was living in Hartford, Conn. This we did. Alfred wanted me to remain with him, as I could get plenty of work and good wages, so I spent the summer there.

In the fall, my brother-in-law, John Berry [Hannah's husband] came along and wanted me to go to Wisconsin with him to see the country. Alfred was away from home at the time, but I packed my trunk and left for the West without bidding him good-bye, and never saw him again.

The Erie Canal had been completed in 1825 and with it a connecting waterway from New York City to the Great Lakes region. Horace Greeley's admonition "Go West, Young Man" seemed to whisper in many a young man's ear. In 1844 railroads were being built connecting the Atlantic with the Ohio region.

EB: John Berry and I came to Cleveland, Ohio. The lake froze over and we had to spend the Winter there.

The fact that Edward does not mention traveling either on the Erie Canal or by rail suggest these new and exciting modes of transportation were probably not used. It seems most likely the 600 mile trek from Hartford, Connecticut to Cleveland, Ohio was made on horseback. Their trip probably went to New York City and then across the roadways of Pennsylvania.

CHAPTER 2 The Mormons

"Then I knew why it was that I had

been led from my father's house and left

my mother whom I loved dearly."

Edward Bunker

Kirtland had been a rural trading center of about a thousand people prior to 1831. In January 1831 the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormon Church), which was less than a year old, moved its headquarters from New York State to Kirtland, Ohio. It was to be a temporary gathering place until a permanent place could be found. In five years the population grew to over 3,000 and from 1833 to 1836 a temple was built. During this same time, the Mormons were also gathering at Jackson County, Missouri.

In 1837, a general bank panic swept the country and the Kirtland bank failed, closing its doors in November of that year. Joseph Smith took blame for the economic problems and left Kirtland in January of 1838 for Missouri. The main body of the church gradually left Kirtland and moved to Far West, Missouri, leaving behind a few members, including Martin Harris.

The murder of Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet, in June of 1844 may have stimulated new interest and fascination in Kirtland. It may have been a popular place to visit and get away from the routine of the day. Discussion might well have centered on the temple in Kirtland and reported "revelations" that had occurred there.

EB: I went to Kirtland to visit friends and see the temple. While there we met Martin Harris, who invited us to his house, where we went and heard him bear his testimony to the truth of the Book of Mormon.

Martin Harris was the first scribe to assist in the translation of the Book of Mormon from the original golden plates, and mortgaged his farm so the Book of Mormon could be published. He was one of the "Three Witnesses", who testified they had seen an "Angel of God" and the "Golden Plates" from which the book was translated. His testimony, with that of the other witnesses, was published with the Book of Mormon.

The testimony of Martin Harris to Edward Bunker was undoubtedly electrifying. Others who heard his testimony recounted that he appeared to be "a man with a message, a man with a noble conviction in his heart, a man inspired of God and endowed with divine knowledge."

The book, A New Witness for Christ in America, recounts the testimony of Martin Harris as follows:

"Do I believe it! Do you see the sun shining! Just as surely as the sun is shining on us and gives us light, and the moon and stars give us light by night, just as surely as the breath of life sustains us, so surely do I know that Joseph Smith was a true prophet of God, chosen of God to open the last dispensation of the fullness of times; so surely do I know that the Book of Mormon was divinely translated. I saw the plates; I saw the angel; I heard the voice of God. I know that the Book of Mormon is true and that Joseph Smith was a true prophet of God, I might as well doubt my own existence as to doubt the divine authenticity of the Book of Mormon or the divine calling of Joseph Smith."

The witness to the previously stated testimony recounts:

"It was a sublime moment. It was a wonderful testimony. We were thrilled to the very roots of our hair. The little man before us was transformed as he stood with hand outstretched toward the sun of heaven. A halo seemed to encircle him. A divine fire glowed in his eyes. His voice throbbed with the sincerity and the conviction of his message. This was Martin Harris whose burning testimony no power on earth could quench. It was the most thrilling moment of my life."

Edward must have come away from his visit with a similar feeling and a desire to investigate further.

EB: I obtained work at Cleveland for eight dollars a month and board. While in Cleveland, Mr. Berry found the Book of Mormon, read it, and brought it to me to read, which I did. John Berry left me and went to Pittsburgh to obtain work and we agreed to meet in Wisconsin. The man with whom I was living had the "Voice of Warning", which I read also. I found a branch of the church there, attended the meetings, became convinced of the truth of Mormonism, and was baptized in the month of April, 1845. Then I knew why it was that I had been led from my father's house and left my mother whom I loved dearly.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Days Saints was only 15 years old in 1845. It had been persecuted wherever it went due to some unique beliefs and a requirement of total commitment from those who joined. The Church had grown rapidly and the promise of a better life touched many.

A Voice of Warning was a pamphlet written in 1837 by Parley P. Pratt, one of the high ranking Apostles of the Church. It's title page stated "Instruction to all people or an introduction to the faith and doctrine of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints."

The preface begins: "During the last nine years, the public mind has been constantly agitated, more or less, through all parts of our country, with the cry of `Mormonism, Mormon-ism, Dilusion, Imposture, Fanaticism,' etc., chiefly through the instrumentality of the press. Many of the newspapers of the day have been constantly teeming with misrepresentations and slanders of the foulest kind, in order to destroy the influence and character of an innocent society in its very infancy; a society of whose real principles many of them know nothing at all."

"The object of this publication is to give the public correct information concerning a religious system which has penetrat-ed every state from Maine to Missouri, as well as the Canadas, in the short space of nine years; organizing Churches and conferences in every region and gathering in its progress from fifty to a hundred thousand disciples."

The pamphlet contained seven chapters addressing various aspects of the doctrine of the Church. Two quotes from the text seem significant in relation to Edward's life. In the first chapter the author contends that only a literal interpretation of the Bible is correct.

This is followed early in the second chapter where the author states: "But O! kind reader, whoever yea are, if you are not prepared for persecution, if you are unprepared to have your name cast out as evil, if you cannot bear to be called a knave, an impostor, or madman, or one that hath a devil; or if you are bound by the creeds of men to believe just so much and no more, you had better stop here." The point is driven home with: "Indeed, it is our firm belief in the things written in the Bible, and careful teaching of them, that is one great cause of the persecution we suffer."

This then was the basis for Edward's belief in this new religion: (1) A prophet was leading the church and as such had translated the Book of Mormon from an ancient record, (2) The Bible was correct and a literal translation of such was required, and (3) Persecution would surely follow anyone with a committment to this new belief. After investigating the doctrine and meeting with the people, Edward so deeply believed that he gave his whole heart to the venture.

EB: After the lakes were opened, I got higher wages, $16 a month at Akron where I worked one month. Then I went aboard a boat and landed at Chicago, then a small frontier town. From there I went to Rock River, Wisconsin, to visit my cousin Patience Millet, and friends from Maine. After the time was spent there, during which time I told them I was a Latter-day Saint, they accused the Mormons of believing in polygamy. I told them it was only a slur and a false statement. At the end of my stay, I took the stage to Galena, ninety miles distant, and then aboard a steamboat, went down the Missis-sippi River and arrived at Nauvoo in July 1845.

Nauvoo was a city that stood on a bold point half encircled by the placid yet majestic Mississippi River. From the banks of the river the ground rose gradually for at least a mile where it reached the level of the prairie that stretched eastward in luxuriant growth of natural grasses and patches of timber. The city was on the west edge of Illinois and about 190 miles north of St. Louis on the Mississippi river.

When the Mormons were driven from Missouri in 1839 they purchased land at Commerce, Illinois. It was a disease-ridden swamp land which they drained, laid out into a square grid of ity blocks, and dedicated Nauvoo-the-Beautiful.

The Mormons began to build another temple and were gathering in great numbers. An estimated 25,000 Mormons lived in Nauvoo and surrounding villages by 1844. Persecution followed the Mormons. It continued until it culminated in the martyrdom of Joseph Smith, their leader, at Carthage Jail, Illinois, in June of 1844.

When Edward arrived in Nauvoo in 1845, the city was in a state of semi-chaos. Several individuals claimed succession to Joseph Smith and leadership of the Church. Factions had broken away, but the greatest number remained under the leadership of Brigham Young and the Apostles. There were continuing attacks from individuals and groups in the surrounding communities. Mormons living in the outlying areas saw their homes burned and were chased into the city.

EB: I had a letter of recommendation to George A. Smith, who was in council with his brothers, but came out and spoke to me and asked me what I was going to do. I told him I did not know, but wished to do whatever was the best. He asked me if I had any money. I told him I had some. He advised me to hire my board and go to work on the temple, or Nauvoo House. So I hired my board and went to work on the temple. I paid my tithing from the day I was baptized every tenth day and the tenth of the worth of my clothes. After having paid my tithing, I went to work for the Nauvoo House, cutting hay for them on the prairie with two of the brethren. We camped where we worked until the mobs broke out and began to burn the farms and drive the Saints into Nauvoo. I joined the militia and went out as a guard to assist some of the Saints to move in. I was in the infantry company that went by order of the Sheriff of Bannock County to make arrests of those who had been burning and plundering the homes of the Saints.

In late 1845, armed mobs continually threatened the lives of the Mormons. Finally, in February of 1846, about 16,000 Mormons evacuated Nauvoo. They went west, crossing the Mississippi River on the ice and in ferries. It must have seemed like the children of Israel in their exodus from Egypt: The Mormons took 3,000 wagons, 30,000 head of cattle, and great numbers of horses, mules, and sheep.

EB: The presiding priesthood compromised with the mob and agreed to leave Nauvoo. Then I crossed the river to Montrose and went to work for Peter Robinson, threshing grain and making flour barrels.

While at Montrose, Edward Bunker met Emily Abbott. She was born September 19th, 1827 at Dansville, Livingston County, New York, the oldest child of Stephen Joseph Abbott and Abigail Smith. Her father owned a woolen mill that converted wool to broadcloth. They lived in a large two-story frame home and sent Emily to the best grammar school available.

Stephen Abbott, being caught up in the spirit of westward emigration, heard of the rich farm land of the Mississippi Valley. After traveling to Pike County Illinois, he bought 160 acres of farmland and 40 acres of timberland and then returned for his family. In 1837, when Emily was not quite ten years old, her family left New York state traveling down the Allegheny River in a five week trip that eventually took her to a new home in Illinois.

Two years later, in 1839, her family came in contact with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and was baptized. The Mormons were gathering at Nauvoo, Illinois and the Abbott family sold their holdings and, in 1842, joined with the others there. Stephen Abbott became good friends with James Brown, and upon learning of polygamy they vowed to each other that if one should die, the other would marry his widow and care for her and the children. Both had large families at the time: Stephen Abbott had eight children, six girls and two boys.

Music was loved by the Abbott family. Stephen became the bugler in the Nauvoo Legion, the local military. Young Emily, who could never remember tunes very well before, would love to sing the songs she heard at the meetings.

In October of 1843, Stephen went to gather cord wood from a small island in the Mississippi River. While so engaged he contracted pneumonia and died on the 19th. The loss of their father and husband was devastating to the family. A few months later the Prophet Joseph Smith was martyred, and Emily's world was turned upside down.

Each member of the family had to help out with sustaining the family. Since Emily was the oldest she sought employment outside the home. She obtained work with several families, one of which was Thomas King. Here she acquired the skills of a seamstress and tailor and met Edward Bunker. The devastation and hardship of the past was tempered by this newfound friendship and romance.

EB: While at Montrose, I became acquainted with Emily Abbott and we were married in Nauvoo by [Apostle] John Taylor, February 19, 1846, just before Brother Taylor crossed the river to join the Saints at Sugar Creek.

At the time of the exodus from Nauvoo, Captain James Brown took Emily's mother, Abigail, as his wife. He was an important figure in the community and had other responsib-ilities, but did all he could to assist the Abbott family. During Brown's frequent absences, Edward stepped in to offer leadership and assistance to the Abbott family.

EB: After my marriage, not being plentifully supplied with this world's goods, I went down the Mississippi to Keokuk. There I obtained a job cutting cord wood at 50 cents per cord, boarded myself, camped in the timber, did my own cooking, and cut 15 cords of wood a week. I worked about three weeks and obtained enough money to buy a few of the necessities of life.

I returned home and Brother William Robinson offered to take myself and wife West on condition that I drive and care for the team and Emily assist with the cooking. We agreed to do this and journeyed westward with the main body of the Saints.

When we got to Garden Grove, Mr. Robinson concluded he couldn't take us any farther, so we remained there. With the help of Brother Steward, a young man who had just been married, I bought a log cabin of one room. We put a roof on it and chucked it, but it was minus doors, floor or windows. We moved our wives into it and I went to Missouri with the intention of earning money enough to buy a team and wagon.

I was in company with two other brethren, and being unable to reach the nearest town, thirty miles distant, we camped the first night in the woods without blankets or fire. The mosquitoes were very bad. Arriving at my destination, I worked one week for corn and bacon.

At this time the report reached us that the United States government had called for a company of Saints to go to Mexico. I did not believe it, but the spirit of the Lord directed me to go home. So the following Saturday, with the side of a bacon slung over my shoulder, I started for home, thirty miles distant.

As I neared my destination, I met some brethren hunting stock and they confirmed the report I had heard concerning the call for a battalion to go to Mexico. They also told me that Brigham Young had written a letter to the Grove calling on all the single men and those that could be spared to come to the Bluffs, 140 miles distant west, to assist the families and care for the teams of those who had joined the battalion, and they in turn could have the use of their teams to bring their families to the Bluffs.

Next day being Sunday, I went to meeting and heard the letter read. Volunteers were called for and I was the first to offer my service. Eight others followed my example. They agreed to meet me at my house the following Tuesday morning at nine o'clock and we would start together for the Bluffs.

Tuesday morning came, but none of the men who had agreed to meet me put in an appearance, so, with my small bundle of clothes and provisions, I started alone on the journey of 140 miles, and only one settlement on the way. When within two days journey of the Bluffs, I overtook Mr. Robinson, who had left us at Garden Grove. He had lost a child and his teamster had deserted him, so he besought me to drive his team on to the Bluffs, which I did.

When within ten miles of our journey's end, a messenger came into camp about midnight with the information that 16 men were wanted to complete the battalion. The camp was called up and not one volunteered until I broke the ice. Soon others followed and the required number made up.

When Edward left Emily, it was under the assumption that he would be back a short time later with a team to assist in the migration. The next thing she knew, he was in the battalion and on his way to Mexico. Emily and her mother's family were left to care for themselves until Edward returned. They, with other families of the proposed battalion, were scattered in a string of camps for hundreds of miles across Iowa. They were to depend on their own initiative and the help of friends for their survival, with no certain gathering place designated, and no immediate prospect of a permanent settlement.

It would be easy to criticize Edward for this lack of concern for his wife, but one has to realize that they both were firmly committed to this new faith. The doctrine of the church promised great and marvelous spiritual blessings to those who would sacrifice their personal needs for the building of the kingdom on earth. Edward felt this sacrifice was his duty and that the Lord would protect and provide in his absence.

CHAPTER 3 The Mormon Battalion

At Council Bluffs, President Young gave a farewell address to encourage those who had enlisted. He assured them that their families would be cared for, and fare as well as his did, and he would see that they were helped along. He predicted that not one of those who had enlisted would fall by the hands of the nation's foe, that their only fighting would be with wild beasts. This undoubtedly was of some reassurance to Edward as well as the rest of the battalion and their families.

EB: The next morning [July 22, 1846] we filed out of camp and went to Trading Point on the Missouri River, where the Battalion was camped for a few days. We took up our line of march for Fort Leavenworth.

The Battalion reached St. Joseph, Missouri on July 29th, 1846 and on August 1st arrived at Fort Leavenworth, on the Kansas side of the Missouri River. The company included 549 officers, privates and servants. Families also traveled along in wagons as a support staff.

A company of Missouri volunteers called the Dragoons, had just left Fort Leavenworth headed for Santa Fe, under the direction of Colonel Doniphan. A separate regiment called the "Missouri Volunteer Cavalry" would accompany the Battalion. How ironic that Mormons were to share the trail with the bitter enemy who had recently driven them from Missouri.

The paymaster at Fort Leavenworth was surprised at striking differences between the Mormons and the Missourians. Every man in the Mormon company was able to sign his own name to the payroll. Only about one in three of the Missouri volunteers could put his signature to the document. The paymaster also noted that the members of the Mormon Battalion were generally more intelligent, submissive and obedient to their commanding officers.

EB: We received our arms and camp equipage. We had the privilege of drawing our clothes or the money in lieu thereof. Most of the Battalion men received the money and sent the greater portion of it back to our families.

The objective of the Battalion was to reinforce Kearney's army in California and to build a supply route from Santa Fe to California for future military operations. Each soldier received forty-two dollars. They carried with them clothing, bedding, a few rounds of ammunition, a knapsack and a canteen that held three pints of water. Wagons carried tents which the men slept in by night.

EB: We moved out a short distance from Fort Leavenworth and went into camp waiting for Col. Allen, who was sick at the fort. On learning that Col. Allen was dead, Lieut. Smith was given command of the Battalion and he put on a forced march to Santa Fe [beginning August 14, 1846].

A few days out from Ft. Leavenworth quite a number of the Battalion took sick with chills and fever. Doctors Sanderson and McIntyre were assigned to the company. Dr. Sanderson, or as the company would come to call him, "Doctor Death", was the senior physician and threatened with an oath to cut the throat of any man who administered any medicine without his orders. Dr. McIntyre was a good botanic physician, but was restricted by the command. Some of the Battalion members felt at times that even Lieutenant Smith was subservient to Dr. Sanderson's will.

Each morning the sick were marched to the Doctor's quarters where "wicked cursing" accompanied the administration of calomel and arsenic from the "Old Iron Spoon". These were nearly all the medicines he utilized except for a concoction of bayberry bark and camomile flowers which he used as "strengthening bitters". Needless to say, several died along the way as a result of the offered cure.

The battalion followed the Santa Fe Trailwhich was first carved by William Becknell in 1821 and had since become a two-way thoroughfare of international trade. It proceeded diagonally across Kansas through the Oklahoma panhandle to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

During this early part of the trek they came upon buffalo. To emigrants from the east the scene was overwhelming, for as far as the eye could see roamed herds of majestic buffalo. They turned the plains into a "shaggy rug." Edward must have gazed in awe at the sight.

By mid-September they left the Santa Fe Trail and the Arkansas River at a point were Dodge City now stands. Here the commanding officer insisted the accompanying families not specifically enrolled as part of the battalion should be detached and sent under a guard of ten men up the Arkansas River to Pueblo, a settlement in the southeast corner of the present state of Colorado.

The battalion then took a short-cut across the "Jornada " or Cimmarron desert to the Cimmarron River. This was a "rattlesnake ridden hot-bed of Indian warfare." The Comanche, a powerful and ferocious tribe, would attack a halted caravan of wagons, stampede and steal the stock and possibly attack the camp. The Indians would likely avoid a well-armed battalion of soldiers; and with any luck this route would be faster than the Santa Fe trail, which circled the desert.

Edward had been an enlisted solder for two months now. He was twenty four years old and probably in better physical condition than many in the company. Surely he was torn between concern for Emily, coping with the hardship of the trek, and anticipation of the great adventure of the new frontier.

During the latter part of September the men were reduced to two-thirds rations. The only drinking water was "brackish" and many of the men became sick with what was called "summer complaint". The main source of fuel for camp fires was buffalo chips which became harder to find as they moved through the desert.

On the 24th, they came across a human skull and the bones of one-hundred mules that had perished in the elements. That night they encountered and camped with a company of traders going south to Santa Fe.

The next day they marched twenty miles over a rough and mountainous road and finally arrived at Gold Spring. There they found good water and saw timber for the first time in several days. On the following day they saw deer, elk and antelope and reached Cedar Springs by nightfall.

As they left the monotony of the barren plains, some of the men saw real "mountains" for the first time. Edward had grown up by the White Mountains, but what he approached now were much larger and majestic.

The teams and men were growing more and more weary. Each night the battalion pitched their tents on a four to six acre area, sometimes by good water and other times by stagnant water. The men attributed the hardship to the lack of three basic elements: (1) Food, (2) Water, and (3) Judgement on the part of their commander.

As October came the men marched on, passing within half a mile of an ancient structure. As they marched they gazed to the north to see what had once been a castle, fortification or other large building. It was almost 200 feet long and averaged four feet high with rock laid in cement. The whole countryside appeared to have been fashioned with an elaborate canal system that irrigated the once-fertile land.

On reaching the Red River the company was divided into two divisions: The first, containing the strongest and most able-bodied men, went ahead; The second, containing the women and sick, followed more slowly. The first arrived at Santa Fe on the 9th of October and the second on the 12th.

Upon arriving at Santa Fe, the first detachment was received by a salute of one hundred guns by order of Colonel Doniphan, a steadfast friend of Joseph Smith and the Mormons during their troubles in Missouri.

Santa Fe gave Edward his first taste of western Mexican-American culture. It must have been an eye-opening experience for the young devotee. With a population of 6,000, it was the oldest seat of government in the continental United States. It predated Plymouth colony by 10 years. The main square was a market and meetingplace where ranchers brought produce loaded on donkeys. Spaniards, Americans, Mexicans, and Indians mingled there by the one story adobe governor's palace surrounded by flat topped adobe houses. Fresh and dried fish could be obtained in the nearby Indian pueblos.

The town was a wide-open wild west Spanish town with saloons, gambling houses, dance halls, sport centers (for cockfights) and alluring retreats where "warm-blooded Spanish and Mexican women sold love at a price". The Mormon men restrained themselves and were busy in preparation for the coming trek. They outfitted six large ox wagons, four mule wagons, plus five mule wagons for each company. Teamsters were assigned to each.

EB: When we got to Santa Fe we drew all of our money and sent a portion of it back to our families. [On October 13th, Captain] Cooke was left at Santa Fe by order of General Kearney to take command of the Battalion and lead it to California.

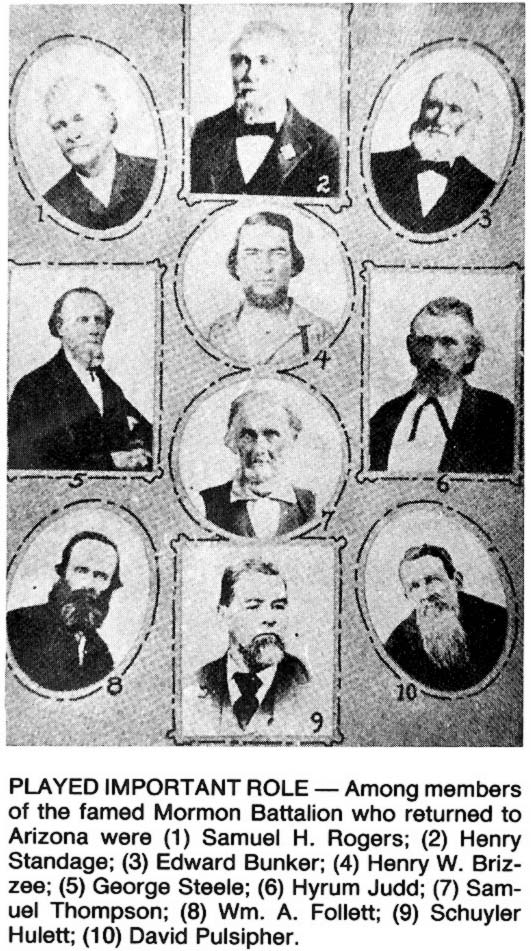

At Santa Fe I was detailed as assistant teamster to Hyrum Judd. By so doing I did not have to carry my gun and knapsack and was exempt from guard duty. One detachment of the Battalion consisting of the women and [86] sick men were sent on Sunday Oct. 18th, to Pueblo under the command of Captain James Brown to Benton's Fort to winter.

The Battalion left Santa Fe on Monday, October 19th, following the Rio Grande River to the south. There were three guides assigned to the unit. One of them was Jean Baptiste (Pomp) Charbonneau, the son of Sacajawea and a Canadian Frenchman. Captain Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition had wanted to adopt Jean and raise him as his own, but that never occurred. In 1823, while living with his father in Kansas, Jean met a German Prince who took him to Germany. "In a castle near Stuttgart, Pomp lived among royalty, received additional education as well as training in court behavior, and traveled with the prince throughout Europe and North Africa. He returned to the American West in 1829 and spent the next seventeen years ranging with Jim Bridger and other mountain men. Edward was a recipient of the vast experience of Pomp Charbonneau and the military training of Colonel Cooke.

Lieutenant Colonel P. St. George Cooke, was born in Virginia in 1809. He gradutated from West Point in 1827 and served continuously in campaigns in Illinois and Kansas before taking command of the Battalion in Santa Fe. Colonel Cooke was a strict and impartial "letter of the law" disciplinarian. Where Lieutenant Smith, who led the march to Santa Fe, was sometimes perceived by the troops as weak, Colonel Cooke was definitely not. The contrast in leadership styles and effectiveness must have proved educational for Edward.

As the battalion proceeded south it suffered a great deal from excessive marches, fatigue and short rations. A few fat cattle were taken along, which the company thought were to be used for food. But the Colonel informed the troops that the animals were intended to work and were only to be slaughtered after they failed from sheer weakness and exhaustion.

From that point forward, the work animals were killed as they gave out and the carcasses issued as rations. No portion of the animal was thrown away that could possibly be utilized for food. "Hides, tripe and entrails" were eagerly and completely devoured, often without water to wash them down. The bone marrow was considered a luxury, and issued in turns to the various camps.

On November 10th, a detachment of 55 sick men under the command of Lieutenant W. W. Willis was separated from the main body and started back to Pueblo.

On approaching the Mexican border Colonel Cooke was, to quote David Crockett, "dumbfounded". There appeared to be some confusion about the direction to pursue. The current course appeared to be taking the battalion toward Mexico and not California. Gloom fell over the entire group. All their hopes, conversation and songs, since leaving Nauvoo, had been centered on California and the expected reunion with families and friends. That night Edward and over three hundred others offered fervent prayers to have the direction changed.

The next day, after traveling a short distance, the Colonel ordered a halt. "This is not my course--I was ordered to California," He said with firmness. Turning to the bugler, he said, "Blow the right."

"God bless the Colonel!" James P. Pettegrew burst forth.

The Colonel turned and with a penetrating glance surveyed the troop for the source of the comment. For once, his stern face softened and showed signs of satisfaction.

Late in November, the main body reached the summit of the Rocky Mountains. Edward was familiar with the mountains in the east, but this must have been a thrilling experience to be standing on top of the world. From this point forward the waters all ran to the west instead of the east. Edward had reached the gateway to the Pacific.

In early December, as they continued down the San Pedro River, the advance soldiers came upon hundreds of wild cattle. They were directly ahead in the line of march. The rumblings of the approaching battalion wagons startled the cattle, dispersing them in various directions. Some, to gratify their curiosity, moved towards the battalion.

They were terribly beautiful and majestic which prompted the soldiers to ready their muskets in case the animals turned on them. Cattle that were clearly visible from some distance ran away, but those which came upon the battalion suddenly wheeled and charged. From one end of the line to the other the roar of firing muskets was almost deafening. Some estimated that over eighty bulls were killed on the spot.

Corporal Frost was on foot near Colonel Cooke who was on horseback, when an immense coal-black bull came charging from some hundred yards away. Cooke ordered Frost to run for safety, but instead Frost, in a protective effort, very deliberately aimed his flintlock and fired when the beast was "within six paces." The bull fell headlong almost at his feet. Cooke said of Frost that he was "one of the bravest men he ever saw."

Contrast this with the tale of another man who "shot six balls into one bull, and was pursued by him, rising and falling at intervals, until the last and fatal shot, which took effect near the curl of the pate." As these stories were retold around the campfire, Edward surely reflected at the contrast in method and outcome. One obviously inexperienced man repeatedly attacked the problem until it was resolved, the other, with ability and knowledge, calmly and quickly executed the task. The difference seemed striking.

The Battalion anticipated some rest and relief at Tucson, but the town of four or five hundred was protected by a force of two hundred Mexican soldiers. They were under order not to allow a U.S. armed force to pass through without resistance. Before a battle could be waged, the soldiers and citizens fled the town and the Battalion passed through without confronta-tion or a chance for relief.

The Battalion left Tucson in mid-December and the remainder of the month it suffered almost beyond human endurance. Lack of food and water, in addition to overmarching, caused substantial hardship. The education Edward received from this experience was purchased with pangs of hunger and the struggle to continue.

Toward the end of December the group arrived at a Pima Indian village and camped the following day by a village of Maricopa Indians. Generally, Indians were a scourge and not well regarded by many, but these were hard working and generous. Great praise was heaped on them by the men.

January of 1847 saw the Battalion reach the Colorado River and arrive near San Diego, California. At least 14 of the Battalion had died along the way. Having enlisted in July of 1846 for a twelve-month period, they had marched over two thousand miles, but their term of enlistment would not be complete for another six months.

Tyler reported the following statement made by Colonel Cook on January 30th:

"History may be searched in vain for an equal march of infantry. Half of it has been through a wilderness where nothing but savages and wild beasts are found, or deserts where, for want of water, there is no living creature. There, with almost hopeless labor we have dug wells, which the future travelers will enjoy. Without a guide who had traversed them, we have ventured into trackless tablelands where water was not found for several marches."

"With crowbar and pick and axe in hand, we have worked our way over mountains, which seemed to defy the wild goat, and hewed a passage through a chasm of living rock more narrow than our wagons. To bring those first wagons to the Pacific, we have preserved the strength of our mules by herding them over large tracts, which you have laboriously guarded without loss. The garrison of four presidios of Sonora concentrated within the walls of Tucson, gave us no pause. We drove them out, with their artillery, but our intercourse with the citizens was unmarked by a single act of injustice. Thus, marching half naked and half fed, and living upon wild animals, we have discovered and made a road of great value to our country."

EB: On the 27th of January we reached San Luis Mission where we remained a short time. Then we moved up to Los Angeles [Mar. 19] at which place we remained until we were discharged on the 16th day of July.

The dragoons accompanied the Battalion to Los Angeles. On arrival the dragoons camped in town and the Battalion on the eastern edge. The Battalion was ordered to finish erecting Fort Moore, an earthen barricade, on a hill above the plaza of Pueblo de Los Angeles. The Fort stood eighty feet above the old Plaza Park and Olvera Street, the old Mexican business district.

When members of the battalion would venture into the wild and rough town among the native Mexican population, bullies would begin to "impose on the Mormon boys." The dragoons would intercede and say: "Stand back; you are religious men, and we are not; we will take all of your fights into our hands," then with an oath would say: "You shall not be imposed upon by them."

Company B, which had been stationed at San Diego, arrived on July 15th, 1847. The next day at three o'clock, p.m., the Battalion came to formation, with A company in front and E in the rear. Lieutenant, A. J. Smith, inspected the troops and then in a low tone of voice said: "You are discharged." That was all, and the ceremony that closed their days of military service was over.

Following discharge, eighty-one members of the Battalion re-enlisted for six months at Los Angeles and were ordered to San Diego, to act as a provost guard to protect the citizens from Indian raids. The rest of the Battalion organized into companies in preparation for a march towards the East.

Edward had served his country, he had served his God and he had been spared. This one year's experience had taken him through the refiner's fire. He had seen the wonders of the west and experienced a lifetime of adventure. He had established friendships that would last the rest of his days. The term "greenhorn", which meant "farmer who had no idea how to live off wild country", no longer appled to him. But with all the knowledge and wisdom he had gained, he was half-a-continent away from the person he loved and longed for.

CHAPTER 4 To Find Emily Abbott Bunker

The Donner Party left Springfield, Illinois about the same time Edward left Nauvoo Illinois in March/April of 1846. The Donner Party left Independence, Missouri in May; Edward and the Battalion departed from nearby Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas in mid-August.

At Fort Bridger the Donner Party made an ill-fated decision to take "Hastings Cut-off" to the Salt Lake valley and across the Great Salt Desert, a shortcut no one had ever traversed before. The more typical California trail would have taken them to Fort Hall in Idaho and then down into Nevada and the Humbolt River.

They passed through the Salt Lake Valley in late summer of 1846, but in so doing lost precious time. It took them 28 days to travel the last 50 miles into the Salt Lake valley.

The "Cut-off" took them across the great salt desert where they lost 100 oxen and had to abandon several wagons and much-needed supplies. They were a divided, "quarrelsome" group.

Before they reached Truckee Pass, the last major barrier before the Sacramento valley, they were caught in a terrible snow storm. They were helplessly short of supplies and imprisoned in snowy mountain country.

Many of their number perished in the Sierra Nevada Mountains near Lake Tahoe that winter. Some of the survivors subsisted for some time on the bodies of the dead. Forty-two of the original ninety in the Donner Party finally reached Sutter's Fort in the Spring of 1847.

About that same time at Los Angeles, prior to being mustered out of the army, the Battalion men received six months pay. Most used this money to purchase animals, clothing and an outfit for the return trip. Horses and mules were cheap and each member of the returning party purchased adequate provisions for the trip.

In late June Edward first heard of terrible suffering of the Donner Party. There must have been some anticipation of what the returning Battalion soldiers would find when they reached what is now known as Donner Summit.

EB: Having drawn our pay and procured an outfit, we prepared to return to our homes by way of Sutter's Fort and across the North Pass of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the Old Emigrant Trail. The returning men of the Battalion divided into three squads on their return trip, and I was in company with Brothers Tyler, Hancock and others.

In the latter part of August, 1847, the returning company stopped at Sutter's Fort, about one-and-a-half miles from the present city of Sacramento, California. Captain John A. Sutter was desirous of building a flour mill some six miles from the fort and a saw mill about forty-five miles away. He offered jobs to the Battalion men who would stay and work. They also met with some of the survivors of the Donnor Party and heard the horrible account of the suffering. The company rejected Sutter's offer and pressed on for Salt Lake City.

A few months prior to Edward's arrival at the sight of the Donner Party encampment, General Kearney and his troops had stopped at the cabins at Donner Lake in order to collect and inter any remains they found. Near the principal cabins they found two bodies that were nearly intact except the abdomens had been cut open and the entrails extracted. The flesh had decomposed and so the bodies appeared as mummies. One author wrote: "Strewn around the cabins were dislocated and broken skulls (in some instances sawed asunder with care, for the purpose of extracting the brains), human skeletons, in short, in every variety of mutilation. A more revolting and appalling spectacle I never witnessed."

The soldiers dug a large pit in the center of one of the cabins where the remains were collected and interred. The cabins and everything connected to the horrid tragedy was then set on fire. A party of men were detailed for the purpose of finding the body of George Donner at his camp, about eight or ten miles distant. There they found the body, which had been wrapped in a sheet, and they buried it.

Edward and company were next on the site of the tragedy. On September 3rd, 1847 they passed the location where General Kearney's party had burned the remains of the famished emigrants. That evening they reached the place where the rear wagons of the unfortunate Donner Party were trapped by the snow. General Kearney's party had not completely burned or buried every evidence of the incident.

Edward saw for himself the horror of the event. Human body parts were scattered around in different directions: a mangled arm or leg, a skull covered with hair, and even a whole body covered in a blanket. Bones were broken "as one would break a beef shank to obtain the marrow from it." It was a sobering sight. The intense human suffering that occurred was overshadowed by the thought of the desperate acts perpetrated by man against man as a result of hunger. The lessons of the Donner party were graphic and powerful: they lacked leader-ship with experience and resourcefulness, they lacked unity and organization, and they lacked respect for nature's elements and human life itself.

The morning of September 6th Edward and company resumed their journey, and after traveling a short distance met Samuel Brannan. He had journeyed from California to meet the main body of the saints in the Salt Lake Valley and was now returning to meet the Saints arriving by ship in California. That night as they camped together, Brannan told how the pioneers had reached the Salt Lake Valley in safety, but that it was not a place the saints would desire to stay. He was confident the Saints would ultimately travel on to California, probably in the coming Spring.

The following morning, shortly after Brannan left, Captain James Brown and a small party arrived. This was the same James Brown that had married Abigail Smith Abbott as a second polygamous wife [but fifth wife] in Nauvoo after the death of her husband Stephen Joseph Abbott. He had been a member of the Battalion, but left with the Pueblo detachment, which arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on July 27th. He brought the mail. This must have been an enjoyable reunion for Edward to visit with Brown about news of the Abbott family. Edward probably already knew that Emily Abbott was not in the Salt Lake Valley and this meeting with Captain Brown undoubtedly confirmed that.

EB: Brown brought word from Brigham Young that those of the Battalion who had not provisions to last them into Salt Lake Valley had better remain in California during the winter. Some of the brethren [about half] turned back and a few others continued eastward. I was in the latter number.

The eastward-bound battalion members traveled up the Humbolt River, turned north to bypass the great salt desert and pressed on to Fort Hall (near the present city of Pocatello, Idaho). Fort Hall consisted of a stockade of cottonwood logs about fifteen feet high reinforced with clay and enclosed a space about eighty feet square. At opposing corners were two eight feet square bastions provided with portholes for rifles. Inside the stockade were log huts for the accommodation of the men. The Hudson Bay Company occupied the fort at the time of Edward's arrival. From Fort Hall they proceeded south to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake.

EB: We arrived in Salt Lake Valley on the 16th of October, 1847. After resting awhile, we [thirty-two] proceeded on our journey towards the Missouri [with eagerness to meet wives and children]. When I left the valley, I had sixteen pounds of flour to take me a thousand miles and three mules which I took from California to Council Bluffs. The articles I had for a winter campaign [were]: One pair of white cotton pants, a white cotton jacket, and old vest, a military overcoat, which I bought from one of the dragoons, a pair of garments, and a shirt; the latter articles were made from an old wagon cover by Sedric Judd, the tailor of our mess.

The battalion members expected to obtain provisions in the valley, but found the people were struggling for their own subsistence and could spare little. They were informed that Fort Bridger, some 115 miles away, had provisions. They left the valley in good spirits on October 18th, 1847. After witnessing the fate of those who were caught in the Sierra Nevada mountains in winter, it is curious that these thirty-two would embark on a thousand-mile trek with winter coming on. The prospect of once again being with wife and family and caring for their needs was worth risking life itself. Provisions were in short supply at Fort Bridger as well, and so they pressed on with what they had.

EB: On our journey we bought some buffalo meat from the Indians and killed a few of these animals ourselves. On arriving at Loop Fork on the Platt River, we camped for the night and tried to ford the river, but the ice was running so thick that our mules would not try to cross, so we put up for the night. The next morning found us in as cold a northeastern snowstorm as I had ever experienced in the state of Maine.

We stayed in camp all day and ate the last bit of provision we had, even a pair of raw hide saddle bags which I had brought from California on a wild mule. The next morning there was about ten inches of snow on the ground and we started down the river hoping to find missionaries at the Pawnee Mission. That day we killed some prairie chickens which was all we had. Next day we came opposite the mission houses which were across the river from us. Some of the boys commenced to build a raft when, on looking down the river, we saw Robert Harris crossing the ice by means of a long pole. We abandoned our raft and followed his example and crossed the river on the ice. We found the mission deserted and the corn all gathered, but we went into the fields and with our feet gathered a few ears of frost-bitten corn which the Indians had left, and which we ate raw. We went into the houses and stayed all night without bedding. One of the boys brought a frying pan and the corn we didn't eat raw, we parched and ate all we wanted and took the rest to camp with us.

On reaching camp the next morning, we found that one of our mules had got into the water and was so badly chilled that he had to be killed, and we ate all the meat except the lights. Those I tried eating, but they were so much like Indian rubber that I gave up the attempt.

After getting all the company across the ice, we went to the Mission homes and stayed all day. Having obtained a little good corn from the Indians, we took up our line of march for Council Bluffs, 140 miles distant, with the snow from 8 to 10 inches deep. We arrived in Winter Quarters on the 18th of December, 1847, having been gone 18 months.

Three days later the Missouri River froze over sufficiently hard to be crossed by teams and wagons. On reaching Winter Quarters I spent the night with one of my companions thinking my wife was still in Garden Grove where I had left her.

Next morning I went to find Bro. Brown's family and they told me my wife was living a short distance from them. This was good news, I assure you, and I lost no time in seeking out Emily and her mother, Abigail Smith Abbott, who was a widow with eight children. Emily, being the eldest, had been able to move to Winter Quarters with the assistance of William Robinson.

I found my wife, Emily Abbott Bunker, in quite poor circumstances, but with a fine boy eleven months old, my eldest son, Edward Bunker, Jr., born February 1, 1847.

Edward refers to his mother-in-law Abigail Smith Abbott as a widow. At the time Edward wrote the previous quote it was nearly 50 years after the incident. Perhaps his recollection of the fact she was a widow of Stephen Joseph Abbott but re-married in 1846 to Captain James Brown did not occur to him. Abigail lived most of the time as though she were a widow, she received financial support but little companionship from Captain Brown since her separation from Brown when she protested his marriage in 1850 to her daughter Phebe Abigail Abbott. Captain Brown died on September 1, 1863.

CHAPTER 5 Home in Ogden:

"I settled in Ogden City, took

up a farm...built a house of three log

rooms and fenced my farm the first year."

Edward BunkerEB: After resting a few weeks [until January 1848], I got wagons and a harness, hitched up my mules and went to Missouri to work for provisions. I found employment splitting rails for fencing. I earned a fat hog and some corn and returned home. We moved across the river to Mesquito Creek. Sister Abbott moved with us. She had two small boys and we put in crops of corn together. The next spring Mother Abbott emigrated to Salt Lake City. I assisted her to a yoke of oxen.

In the fall of 1848, Abigail and her children arrived in Salt Lake City and moved immediately to Ogden. Captain James Brown, who was Abigail's husband through a polygamous marriage, provided her with a ten-acre site on what was later called Washington Avenue. There he built for her a three-room log house with a dirt roof.

EB: The following year [1849] received from Captain James Brown, the money for the same [yoke of oxen]. With this I bought cattle to assist me to emigrate next season.

My wife Emily Abbott Bunker gave birth on March 1, 1849 at Mesquito Creek, Iowa

to our daughter and second child, Emily Abbott.

EB: I also received three months extra pay from the government and a land warrant which I sold for $150. The emigration to California began next year and corn brought from $.25 to $1.50 per bushel. I had raised a good crop and this assisted me very much to obtain my outfit.

In the spring of 1850, I started to Salt Lake Valley in Captain Johnson's hundred and Matthew Caldwell's fifty, and I was captain of a ten. We followed up the route of the California emigrants on the south side of the Platt River. Nothing of importance happened until we came in the cholera district where the emigrants had died in great numbers and were buried by the roadside.

We found one man unburied lying in the brush. He was given a burial by our company. Our camp was stricken and 18 out of the hundred died from the effects of the cholera. My wife, Emily, and daughter, Emily, who had been born to us the first of March, 1849, on Mesquite Creek, Iowa, were taken very sick, but through the powers of faith and good nursing they soon recovered. At the end of three months we reached Salt Lake Valley, our haven of rest, September 1, 1850.

With a well-provisioned outfit, his wife and children around him, and a journey that had to seem mild in comparison to the Battalion march, Edward must have been very positive about the prospects ahead. As the Bunkers traveled in the wagon train to Salt Lake, they met and became fast friends with William Thomas and Sarah Ann Browning Lang. Both couples had two children and a lot in common.

EB: I settled in Ogden City, took up a farm about a mile from the city on what was then known as Canfield Creek. I built a house of three log rooms and fenced my farm the first year. William Lang owned a farm adjoining mine, also James Brown.

It may be of interest to know a little about the place they selected as their home. Ogden was named in behalf of Peter Skene Ogden, a leader in the trapping and fur trading business with the Hudson's Bay Company. He first visited the area in June of 1826. Trapping continued heavily until about 1840 when the bottom fell out of the beaver market and most of the mountain men withdrew into the hills. In 1843, John Charles Freemont encamped on the Weber River and rowed down it in a rubber boat to the Great Salt Lake, accompained by the famous Kit Carson and three others.

In late 1844 or 1845, Miles Goodyear established on the site of Ogden the only year-long adobe of a white man in the entire territory. Goodyear's fort consisted of a stockade of pickets that surrounded some log buildings and corrals close to the Weber River. It was 35 miles north of the Salt Lake valley on a direct line to Fort Hall, where the Emigrant Trail to California passed.

Shortly after the Mormons emigrated to the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, Mormon scouts traveling north became aware of the Goodyear fort and reported to Brigham Young. The fort was a threat to Young, who wanted a Mormon empire without "Gentile" or Non-Mormon strongholds within close proximity. He immediately was interested in buying the fort.

Captain James Brown arrived in the Salt Lake Valley with the Pueblo detachment of the Mormon Battalion a short time after Brigham Young in 1847. On August 9th, 1847, he and a few others were sent to California to collect some backpay. On their way, they visited the Goodyear fort and inquired about the proprietor's interest in selling. The offer was favorably received. In November Captain Brown returned from California with $3,000 in Spanish and Mexican gold coins from the battalion payroll. Brown struck an agreement with Goodyear on November 25 where $1,950 in gold coin was exchanged for "a deed to the land, all his improvements, seventy-five goats, twelve sheep, and six horses."

Brown moved his family to the little fort Buenaventura on March 6, 1848. Many immigrants that had been associated with the "Mississippi Saints" and wintered with Brown at Pueblo moved to the settlement with him. They settled in a scattered fashion along the Weber River, near the mouth of Weber Canyon, and along the Ogden River in what became known as Brownsville.

In February, 1849 a congregation of Mormons in the region was organized as a Latter-day Saint ward with James Brown as Bishop. Large numbers of emigrants were directed by Brigham Young to settle in the Ogden area, and by 1850 there were over 1,000 people living there. In January of 1850, Lorin Farr, a 27-year-old native of Vermont, was sent by church authorities to live at Brownsville. He immediately became the most influential person in what was designated later that year as Weber County. Brown died from an accident in 1863. The settlement was re-named Ogden City and established as the county seat.

The immigration of 1850-51 was so significant that in 1851 it became necessary to survey the townsite. A city council was organized which consisted of a mayor, four aldermen, and nine councilors, all appointed by the governor and legislature of the State of Deseret, and later confirmed by the people in an election on April 7, 1851.

EB: President Young and Heber C. Kimball came to Ogden in 1851 and organized the stake with Lorin Farr as president and James Brown and William Palmer as councilors. I [Edward Bunker] was chosen a member of the High Council and ordained [a High Priest] by Brigham Young, and Heber C. Kimball set me apart for that calling. I was also a member of the first council of Ogden City.

The organization of the church in a local area consisted of a congregation or "Ward" presided over by a Bishop and two councilors. A group of several wards formed a "Stake" and was presided over by a Stake Presidency consisting of a president and two councilors. Within a stake, twelve men from the various wards were called to act as a "High Council" and administer the affairs of integration and coordination of the various wards. Each of these positions were filled by members of the various congregations and they served without pay until such time as they moved away, became ill or could otherwise no longer serve.

With his call to the High Council, Edward immediately gained community status. The call may have been the result of his commitment as expressed by his willingness to sacrifice and serve faithfully in whatever capacity required. It may have been the result of his growing leadership ability as witnessed by those he had served with. It may also have been the result of his affiliation with James Brown, already an established leader in the community.

Edward wrote that he lived on Canfield Creek between William Lang and James Brown. Emily's mother was given a lot by her husband, James Brown, on Washington Avenue. Canfield Creek crosses Washington Avenue at 34th Street. This is about a mile from 28th Street and the edge of the grid initially laid out for the city. Therefore, we might conclude that Edward lived at about 34th street and Washington Avenue. His next door neighbor on one side was his mother-in-law, Abigail Smith Abbott, and on the other side William and Sarah Ann Browning Lang.

3nd Child: Abigail Lucinda Bunker.

Born: April 15th, 1851, Ogden, Utah

Mother: Emily Abbott Bunker [3nd child]

EB: William Lang died soon after I came there [to Ogden] and I married his widow, whose maiden name was Sarah Ann Browning, June, 1852. She had two girls by her first husband.

Polygamy had been practiced in the church for several years. To enter into this practice several things had to occur. First, the man had to be in good standing in the church and generally in a hierarchical position. The added responsibility of multiple wives was given to those who had demonstrated the ability to handle such a calling. Second, the first wife had to give her consent for the husband to marry another wife. The ideal situation was for the first wife to "give" the husband another wife.

Emily was a very proud person. She undoubtedly loved her husband, but she also probably realized that as her husband gained prominence in the church and community he would be asked to participate in polygamy. She had seen her mother marry Captain James Brown as a polygamist wife, which must have softened her view of the situation.

Now that Edward was on the High Council, there must have been some pressure to find another wife. Sarah Browning Lang had been a friend to both Edward and Emily since their trek across the plains. She already had two children and was now a widowed neighbor in need of the support a plural marriage arrangement could offer. Perhaps some of these facts made her an acceptable selection to both Emily and Edward.

Sarah Ann Browning Lang was born October 10th, 1830 in Sumner County, Tennessee. She was the second of eight children born to James Green Browning and Mary Ann Neal. Her father's older brother was Jonathan Browning, famous for his work as a gunsmith. The two brothers had joined the Mormon church in Illinois and lived in Nauvoo. When Sarah was 17 years of age she met and married William Thomas Lang. The Langs and Bunkers had traveled together as young couples across the plains and had settled on adjoining lots in Ogden. Sarah's two children by her first husband were:

Mary Ann Lang, born January 22nd, 1848, and

Eliza Jane Lang, born September 19th, 1851.

Sarah was a young attractive widow that several men took interest in and offered marriage, but Sarah's father said:

"Sarah, I'd rather you'd marry Edward Bunker. He is a good man--long time friend--he is going on a mission and on William Lang's death bed, Edward promised he would have his [William Lang's] temple work done for him."

Sarah and Edward were married in Salt Lake and President Brigham Young said, "Of course, you know all of Sarah's children will belong to William Thomas Lang." Edward Bunker replied, "I couldn't do any greater work than to raise up a good posterity for my friend William Thomas Lang." In later years, Jim Bunker would comment about the situation, "Yes, but there is a damn lot of Bunker in us."

Sarah Browning Bunkersurrounded by her children

"I think it would be difficult to find

a company of men...who journeyed together

with a better spirit [and] determination,

...to gain intelligence, to treasure up

doctrine, to learn truth, and be

prepared to do good."

William Clayton

EB: In the fall of 1852, I was called to go on a mission to England. There were some seventy Elders called at that time. We started on our mission immediately after the October semi-annual conference and took us to the nations of the earth.

At a special conference held August 28th, 1852 in Salt Lake City, one hundred and six men were called to go forward from Utah to sustain and replace returning missionaries from around the world. Edward Bunker and thirty-three others were assigned to go to England.

With little over two weeks to prepare, a wagon train of seventy three people left Salt Lake on September 15th bound for the east. Included in this number were missionaries and various others going east on business. Generally, there were three men assigned to each wagon: Edward Bunker was assigned to wagon number 20 along with Samuel Glasgow, also bound for England, and Washington L. Jolley, going on business.

It certainly must have been an emotional moment when Edward bid his wives and family farewell for what would be a four year separation. The train moved slowly along the well- traveled Mormon Trail. The first part of the trip passed through the western frontier of Utah, Wyoming and Nebraska. They mostly stayed together, encountering cool weather, trains of emigrants and soldiers, Indians and buffalo in great numbers, and the traditional geological landmarks. Provisions were procured at forts along the way.

Orson Pratt, heading east to Washington D.C. on assignment from President Brigham Young, accompanied the group and gave them almost daily instruction concerning the doctrine of the Church. William Clayton, clerk of the company, recorded: "Brother Pratt has given some very interesting discourses...and both by precept and example, has shed a salutary influence on the minds of the brethren. His course is steady, mild, and evidently full of sympathy."

Clayton wrote that they traveled "full of the spirit of their missions. ....I think it would be difficult to find a company of men....who ever journeyed together with a better spirit; or a set of missionaries who ever went with a more seated determina-tion, and firm ambition to do good...to gain intelligence--to treasure up doctrine--to learn truth, and be prepared to do good." On several occasions Apostle Pratt instructed the missionaries concerning the pre-existence of man, a topic for which he was preparing a text to be published. Besides the great instruction they were receiving, their faith was strength-ened by several incidents that seemed to miraculously save them from disaster.

On October 16th, a few days into Nebraska, they camped for the night leaving their horses guarded by six men. At midnight, a lone horse came galloping into camp with blankets flapping and a large tin cup banging from the saddle horn. Perrigrine Sessions wrote: "The horses took affright and away they went. The sound of their feet was like the roar of distant thunder. This left us with feelings that would be hard to describe, left without teams to pursue our journey. But as the providence of God would direct it, one of our company caught a horse as they passed him, mounted in a moment and went with the band, but could not stop them as the tin cup was rattling all the time. The company supposed that the Indians had got the horses and killed the man."

Edward and his brethren no doubt offered up sincere prayers of deliverance regarding the catastrophe that had just befallen them. Sessions summarized the events of the night: "About four o'clock in the morning he [the lone man] came into camp with all safe and the horse that caused the fright. The horses being in a state of excitement so that it was with much trouble that they could be left in camp until morning."

A second event of deliverance occurred about a week later, on October 24th. Sessions wrote in his diary: "Camped on the bank of the Platt. About dark there was a big fire discovered at a short distance, burning the grass down. With a fierce wind the fire came from five to six miles on down and before we had time hardly to do anything the fire came, the flames at least ten feet high and seemed as though nothing could save our horses and wagons. But as the Lord did direct it--we succeeded and got the horses into the river and as the fire came up when within a few feet the wind changed and blew directly from the wagons and caused it to check its speed and by the greatest exertion we kept it from our wagons and it forged on and left the plains black, yet the heavens lighted by the fire as it was dark and gloomy. Before morning it began to rain hard."